Marilyn Manson: Worst to Best

Perhaps the most ephemeral music act in contemporary cultural history, Manson is better (and worse) than most fans and detractors realise.

Disclaimer and Trigger Warning (physical/sexual/psychological abuse)

In 2021, Brian Warner, a.k.a Marilyn Manson became the subject of controversy when Evan Rachel Wood and other various partners from Manson’s life came forward to accuse him of a litany of abuse dating back to at least 2006. While Manson’s career has suffered tremendously in the wake of these allegations, he continues to record and release new music as recently as 2024. I will make a few scant references to the controversy throughout this article where I believe they are relevant, and it’s certainly worth examining his older material through the lens of hindsight.

I think any claims that Manson has always kept his anger and violence within the confines of the music are ahistorical and a total fabrication. I support the accusers’ right to have their stories heard, I believe Evan Rachel-Wood, and I believe that Marilyn Manson has been abusive to multiple former partners.

When I was 11, I didn’t like music.

I just really did not understand why people cared about it enough to invent the radio and the iPod. My mother had a few CDs in the car, one of which was Gorillaz’ Demon Days. My favourite track on this album was Fire Coming Out of the Monkey's Head, a spoken word piece with a hauntingly simple chorus and a very transparent narrative. Perhaps it was because I was (and am) a huge reader, but I just didn’t have much patience for music. If I have to psychoanalyse the mind of my child self to give this article a proper introduction, I suppose that it felt like music suggested an emotion, and I liked clarity and certainty. When the hero died in a book, I knew to feel sad. What exactly was I supposed to feel when Amy Winehouse bemoaned the loss of a tragic, complicated, messy love? I wasn’t even sure I liked girls yet.

When I moved to secondary school, I met a friend who shall remain nameless. We got along really well immediately.

I had an iPod that had nothing but professional wrestlers’ introduction themes, but he had a mobile phone with internet and proper music.

He showed me two things on his mobile phone very shortly after we’d become friends.

The first thing he showed me was the cover of Marilyn Manson’s fourth studio album, The Golden Age of Grotesque. There was something deeply evocative about that cover, a blurred photo of a man that looked more like a shark in stage makeup. That painted white face against the stark black background gave me the feeling that I suppose most other people felt when they first found a piece of music they liked on its own merits, rather than any emotion they may have attached to it given its inclusion in another form of media.

Once we started listening to the album through a shared pair of plastic wired earbuds that were seemingly designed to be as uncomfortable as humanly possible, I remember getting it. I understood why people made the radio and the iPod. If you’ve ever listened to Marilyn Manson’s This Is The New Shit, I’m sure you’ll agree that this is possibly the funniest reaction anyone has ever had to this particular record.

I went home after school that night and asked him for an exhaustive list of the best Marilyn Manson songs, and so began my affinity for a man whose artistic zenith had largely passed before I was ever born, even though he would continue to be a relatively popular musician throughout my life. I was absolutely fascinated by him. While I still clearly hold an affinity, and a deep love, for the records I consider to be his best, Marilyn Manson was the first musician I listened to and enjoyed!

I was enthralled by the idea that a musician could radically reinvent his musical style and aesthetic persona over and over. From the emaciated Worm to the strangely eroticised Omega to the burlesque iconoclast, each transformation felt like another layer of something deeper, more visceral and personal.

Within the space of about six months, which all academics agree is basically a full lifetime to a twelve-year-old, my musical tastes had changed. Ironically, I became a massive Gorillaz fan, which led me onto other alternative rock artists, and slowly drew me towards rap and R&B in my later teenage years. Marilyn Manson fell by the wayside. The phase I went through, where his music and persona felt like a mirror of my own entirely fabricated rebellious streak where I just understood the world on a fuckin’ deeper level man, burned out. I started to explore new genres and artists, no longer confused or wary of art that didn’t tell me how to feel.

But despite all of this, I never fully let go of him. There was always this strange, lingering connection. I would still follow his career, even if I wasn’t always fully invested in his output. I found myself giving everything he released at least one full listen, almost out of obligation, but also a deep-rooted curiosity. It was as if I couldn’t stop wondering if there would be something in his new music that would give me the same feeling I felt standing in the art block on a Tuesday lunchtime.

Looking back, my fandom of Marilyn Manson is likely something a lot of you can relate to, an artist who was pivotal at a certain point in your life, one I’ve always felt a strange obligation to stay connected to even when I’m not actively listening. It doesn't really matter what he releases; there’s some part of me that has to hear it.

And now I suppose I feel the need to work through some of this emotional baggage by giving my childhood self exactly what he wanted: a guide on how exactly each of Manson’s albums makes me feel.

The second thing my friend showed me was a video of an overweight, middle-aged white man getting sucked off by a cow.

I bet you’re glad you’ve been written out of this anecdote now, aren’t you ████?

This is my ranking of Marilyn Manson’s studio albums, from Portrait of an American Family to One Assassination Under God - Chapter 1.

Eat Me, Drink Me

Let’s get the real shit out of the way first, starting with Manson’s sixth studio album Eat Me, Drink Me. It’s hard to find much to say about this album beyond laying down endless negative adjectives in quick succession, which is perhaps the most damning indictment you can make of a piece of art. Eat Me, Drink Me is awful, point-blank period. Manson is six albums deep and a decade removed from his cultural zenith, out of ideas and full of self-loathing. This is not the same artist who tore out the innards of grunge’s twilight and plunged American pop culture straight into Hell. This is an existentially terrified middle-aged man, right in between his most successful period and his eventual reinvention.

There are brief (and I do mean brief) moments where Manson is within touching distance of former glory, particularly the chorus of If I Was Your Vampire where Manson’s vocals feel charged and tortured, but there is so much utter dross on this record that by the end, you feel very much like nothing can be salvaged.

Manson made a puzzling decision to make repeated and pointed references to the style of vocal performance on this album in interviews. He would lie flat on his back and record the songs from a lying position. I don’t know why you would ever do this, and if you’re ever considering this approach a go, I would suggest listening to this album for about twenty seconds and throwing that particular thought straight in the bin. Manson’s voice sounds absurd on this album. It sounds like a SNL impersonator making fun of him. The vocals are grating, processed to hell and back, layered beyond reason and stomach-churning.

Heart-Shaped Glasses is a particular sore point, not only the worst single Manson has ever released but a strong contender for his worst song ever. The pointed references to Lolita are not cute or funny, and less so in the wake of Evan Rachel-Wood’s allegations. Shitting your pants before someone can accuse you of planning to shit your pants is not a win; you’ve still shit yourself.

There are no high points. This is just bad, bad, bad. Up there with the worst albums I’ve ever had the displeasure of being exposed to. This is what emo sounds like when you make the rash decision to play it in front of your friends and they all silently lock eyes with each other wondering who the fuck invited you.

BEST TRACKS: N/A

The High End of Low

If Eat Me, Drink Me and The High End of Low were the only two albums in existence, The High End of Low would be the greatest album of all time—an indisputable classic that redefines music. But obviously, that’s not the case. I just like driving home the point about Eat Me, Drink Me being absolute dick.

This album directly followed Eat Me, Drink Me, and The High End of Low is undoubtedly a step in the right direction. There’s a greater level of precision, a real direction and honestly, there’s clearly some actual effort being applied here. But for the most part, this album does little to climb above being alright. It feels hollow and artificial; it has no teeth. By this point, Manson and Evans-Wood have parted ways and there’s more than a couple allusions to the demise of their relationship that leave a sour taste, particularly the track Leave A Scar, which now reads like more of a tacit admission of guilt than an artistic expression of feeling rejected and left in the wind.

Manson is absolutely lost in the various soundscapes this album tries on and discards. The acoustically driven Four Rusted Horses is particularly gauche, as is Running to the Edge of the World. Manson’s lyrics are almost entirely lacking any bite or catharsis, and while his vocal performances have certainly improved and not been totally barbequed in post, I can’t say he sounds great here; not least because most of what’s coming out of his mouth sounds like the angry ramblings of a teenager who just got dumped by the love of his life. If there’s anything positive to say, Manson has dragged himself out of his absolutely stomach-churning slump, but not by much.

Manson fans have sometimes offered this record up as a better realisation of Eat Me, Drink Me. While I understand what they’re saying, I can’t agree, mostly because I think that particular comment affords this album praise it does not earn. It’s mostly just very forgettable and impotent, whereas Eat Me, Drink Me was palpably awful.

But make no mistake, Manson is spinning his wheels and getting nowhere. There’s some base enjoyment to the rhythm and pulse of We’re From America, but the lyrics are annoying, even if the chorus has an enjoyable pulse and groove. I get it bro, you’re an atheist, and America isn’t that great. That’s awesome. Can you shut the fuck up now?

BEST TRACKS: We’re From America

Born Villain

When putting this article together, I made the ill-advised decision to listen to these albums in chronological order. So, at this point in my listening, Born Villain started as a desperately needed shot in the arm. But of course, Manson’s ability to let you down is never to be underestimated.

The album’s opener Hey, Cruel World promises a blast of energy that has been absent for about ten years. It’s fast and frenetic and even though it’s not great, at this point I’m grateful for scraps. No Reflection continues the pace, and I start to hold onto the idea that maybe it’s going to get better from here. Maybe the suffering is over.

Then Pistol Whipped starts and I feel like my pitiful, worthless life might never meet its end. A feeling I keep coming back to over and over again when working through his worst material is embarrassment. I feel slightly embarrassed that I’m choosing to take time out of my day to give tracks like this the time of day. Overneath The Path of Misery opens with Manson vocal-frying his way through a laboured extract from Macbeth. Are you taking the piss right now? Why are you ruining this for me?

I feel totally lost trying to pick through this material, it is so void of cohesion and purpose. There are single tracks like The Gardener that feel fresher, at least an attempt to cover new ground, but these are really few and far between here. The best parts of Born Villain are obscured behind material that can only be described as benign.

I’m really bored. I would write more, say more but there’s so little to dig into here. At the risk of sounding like a condescending prick, this is intellectual posturing in musical form. I cannot imagine these albums being interesting or revelatory to anyone who has ever heard any other piece of music before in their life.

We’ve left the very worst in the rearview mirror. Thank God. Get me out of here.

BEST TRACKS: Hey, Cruel World / The Gardener

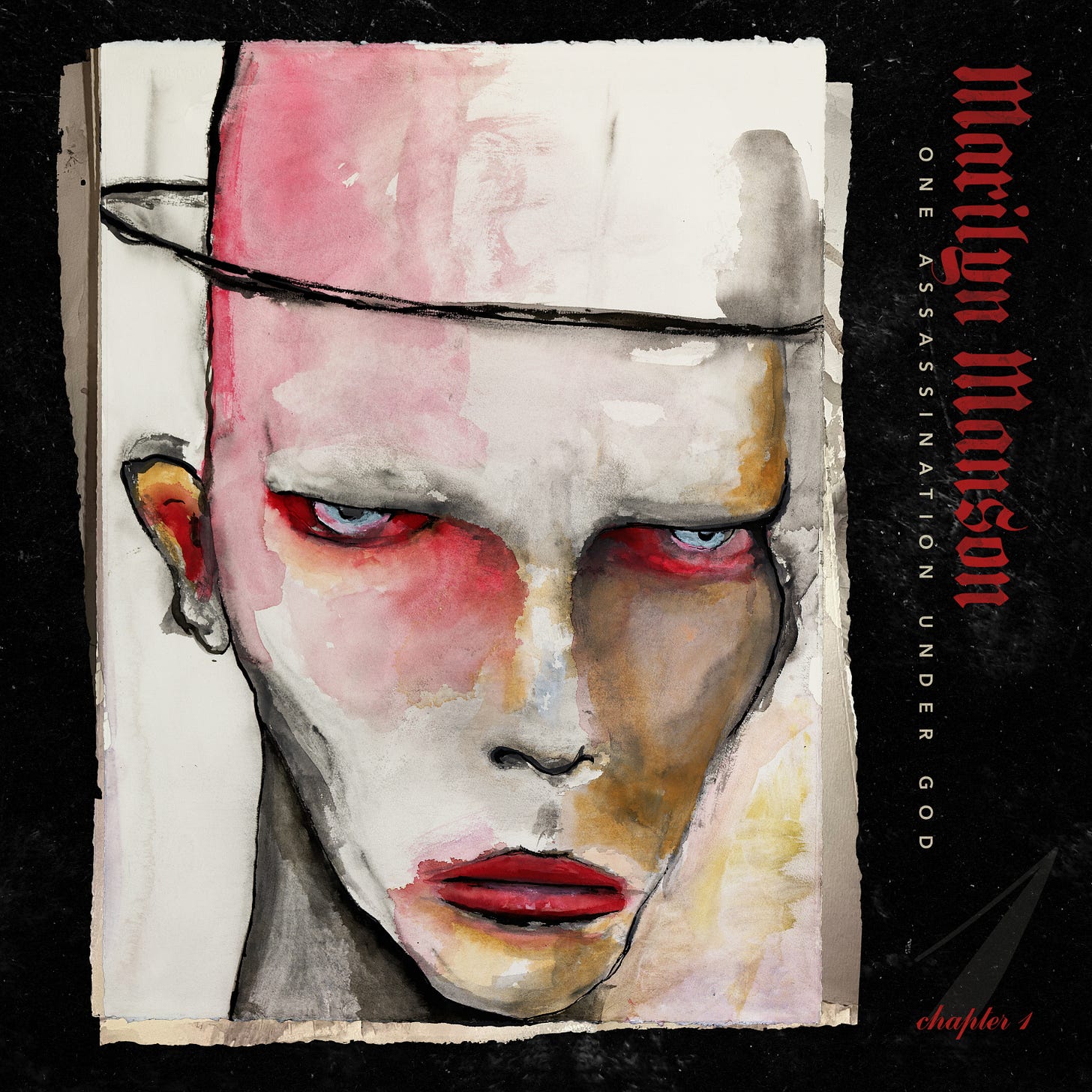

One Assassination Under God - Chapter One

I feel I’ve done a relatively clean job of skirting around the controversy that made Marilyn Manson a hot topic once more in 2021. I don’t think much of his personal life is bleeding into the music in any specific detail until the time of Eat Me, Drink Me: He’s always been an artist who is keen to marry the real world with his artistic vision, and One Assassination Under God - Chapter 1 is no exception.

It feels a little weird for me to go back into his older records and try to retroactively apply the contents of these allegations to records that predate the knowledge of this abusive behaviour by a decade or more. Not because an analysis of that kind is irrelevant or pointless, far from it, but more because I am examining Manson’s career from the perspective of someone who started engaging with it in the early 2010s. By the time I was born, Manson’s cultural zenith had passed. By the time I was old enough to seek out his music for myself on the internet, he was a relic of a bygone era. I wasn’t around for his heyday, and therefore the best I could do when it comes to a historical evaluation would be to regurgitate publicly available information.

But I was here for this. I was an active fan (and a grown man) when these allegations became a matter of public record. As far as the context that informs this record is concerned, I was very much present and aware of all of it. As such, I think it’s important for me to be responsible at this junction: I cannot and will not ignore the obvious elephant in the room.

One Assassination Under God - Chapter 1 is heavier, it’s less accessible than his last two records, but certainly still courting a sound that is safe for the mainstream. However, what sours this record beyond any real redemption is the lyrical content. A lot of tracks like As Sick As The Secrets Within and Nod If You Understand are, in my mind, intentionally skirting the lines between refusing to apologise for Marilyn Manson’s past as an artistic firebrand, and abuse apologia: “What did you expect?”

When Manson says “I won't repent / This is what I was sent here for”, I understand that his explanation for these lyrics would be to say that this is a refusal to apologise for the negative attention he courted in years gone by, and as this album also serves a dual purpose as a sobriety record, the parallels are obvious. However, it also reads in a particularly stomach-churning way when you realise this is the first musical response from a man who has been accused by multiple publicly known partners of a smorgasbord of abuse.

Very little of what is bad about this record has much to do with criticisms the previous entries share, like poor song structure or vocal delivery. I think this sound represents an artistic stagnation similar to the kind Manson was experiencing after the release of Holy Wood, but what makes this record unpleasant for me is the two-faced nature of its lyrical content.

You either did it or you didn’t. But you cannot simultaneously cast allusions to the idea that you’re owning the fact that the self-destructive lifestyle you’ve lived for the majority of your adult life has created chaos for the people who’ve been caught up in it, and cry foul that “Everybody showed up for the execution / But nobody would show their face”.

As a purely musical endeavour, this album is not as bad as the previous entries. It just isn’t, and therefore I can’t mark it among his worst works. Gun to my head, I’d still rather listen to this and ignore the obvious real-world allusions than suffer the indignities of Eat Me, Drink Me and its immediate successor.

But it is uncomfortable and, as selfish as this sounds, it makes me sad. It makes me sad that an artist who had such a transformational impact on my ability to enjoy and engage with music has wound up here. The art cannot be separated from the artist in any of these tracks; Manson’s allusions to the controversy are woven throughout every bit of this. As such, I actually cannot find a single track in here that doesn’t feel too close to the bone for me to look past.

It’s depressing, it’s a bit boring, it’s gross, and I don’t want to think about it anymore. I cannot honestly say that this is the end of my time listening to Manson’s new material: I doubt that day will ever come. But if nothing else, One Assassination Under God - Chapter 1 confirms to me that whatever good can be found in his output, it stops here.

BEST TRACKS: N/A

The Golden Age of Grotesque

Some months ago I started playing a game with friends. Without any context, I played Manson’s cover of Tainted Love, taken from this album, for as long as they wanted (or could stand to hear, in most cases). Then, I would ask them to guess the year of release. Of the ten or so people I surveyed, the vast majority correctly guessed that it was released after the turn of the century but before 2005. Interestingly, everyone who incorrectly guessed the exact year of release gave 2007 as their answer.

What that suggests, I don’t know, but I do know this: The Golden Age of Grotesque might be the perfect post-9/11 artwork ever created.

After two commercial jets are flown into skyscrapers in the heart of America’s most iconic city, killing thousands and triggering a largely pointless, expensive war that would devastate the Middle East with little to no positive outcomes, there’s absolutely nothing terrifying about a thirty-four-year-old man in makeup.

Manson’s shift towards burlesque aesthetic around this time was very entertaining and engaging. But those stylings don’t make much impact on the music itself beyond brief vignettes like Theatre or (imagine a deep inhalation here) Baboon Rape Party. Yes, a thirty-something-year-old thought that was a cool title for an instrumental bonus track. I can find no evidence that a fourteen-year-old boy got the naming rights for this track, so Manson has to bear this particular indignity.

Manson is not unaware of his position as a has-been-boogeyman, openly admitting that “Everything has been said before / Nothing left to say anymore” on the opening lyrics of the record. This is an intensely bold statement to make right before you ask an audience to spend almost an hour listening to your artistic output, and leaves you with relatively few options. Perhaps the most obvious are the following: try to examine where your implied artistic irrelevance leaves you in the landscape of an industry that has gotten used to your once-imposing presence, or have fun. Manson chooses the second, inviting the listener to come and “see the mobscene” just for the sake of it.

The ‘mobscene’ in question, however, is largely a retread of many of the ideas Manson had explored in his previous studio effort, Holy Wood, with less anthems. Holy Wood is marked not only by the sheer number of fun songs but also by Manson’s critiques of consumerist culture: The Golden Age of Grotesque is an attempt to revel in the sheer dumb fun of being a rockstar, but a lot of this album isn’t all that fun. While I’ll stand by This Is The New Shit and Use Your Fist And Not Your Mouth being fun romps, it’s hard not to see languishing and downright embarrasing tracks like Ka-Boom Ka-Boom as the writing on the wall.

Para-Noir too, feels like a missed opportunity, the female vocal track serving as tongue-in-cheek setup for a decadent and indulgent track that Manson buries with a cringe-worthy chorus that descends into self-parody. Manson’s aforementioned cover of Tainted Love feels like a two-pronged low point, not simply a tacit admission that he’s run out of original ideas but a total phone-in, a lazy attempt to recreate the success of Sweet Dreams in the age of nu-metal, a genre Manson seemed to look down his nose at despite failing to provide a compelling counter-offer.

The concept era is over, and the cat is out of the bag. It will take an age for Manson to rediscover a cohesive vision. If you’re planning on revisiting Manson’s catalogue in chronological order, you’d better try your damndest to enjoy this one. It’s the last time you’re going to have fun for about a decade.

BEST TRACKS: This Is The New Shit / Use Your Fist And Not Your Mouth

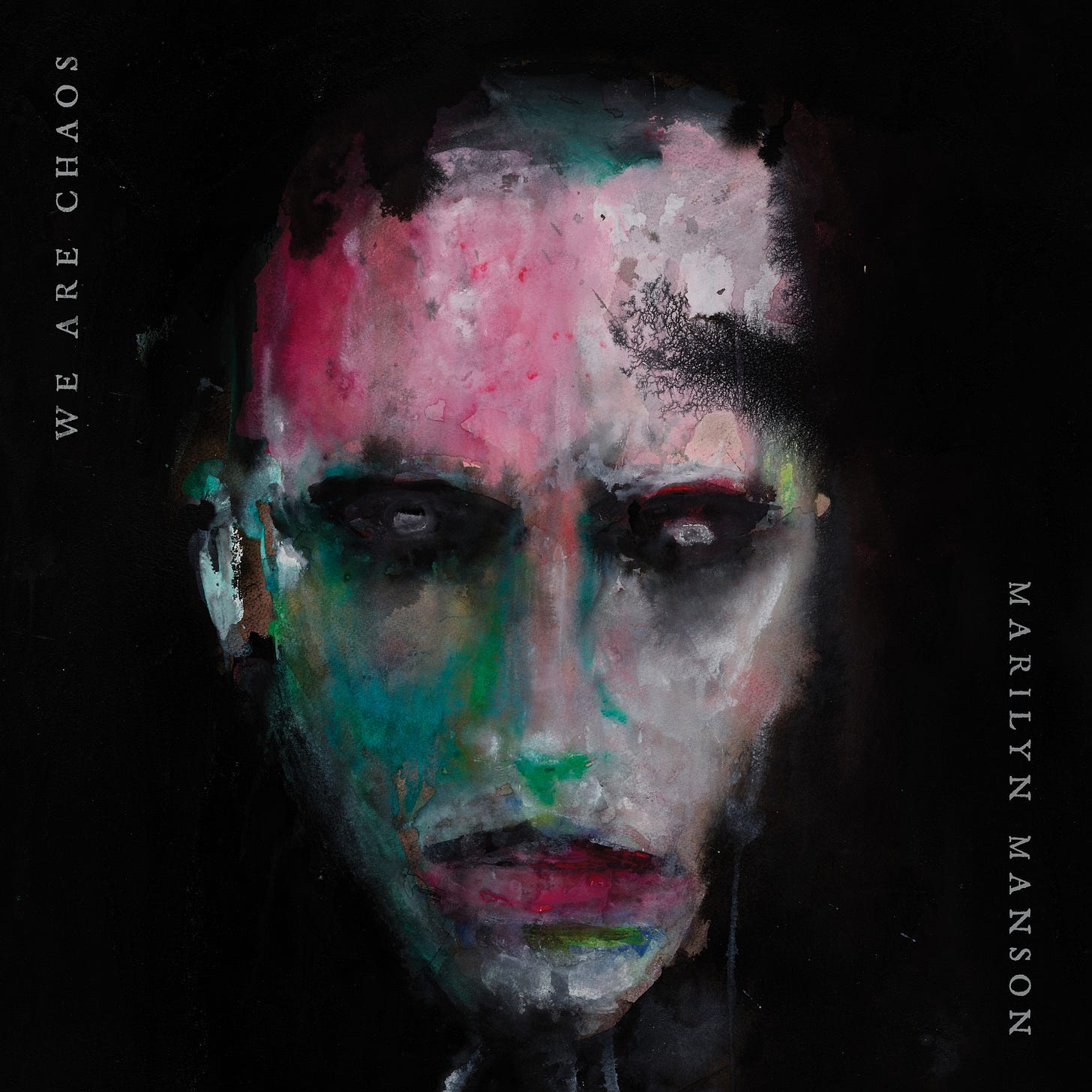

WE ARE CHAOS

WE ARE CHAOS was released during the COVID pandemic, a time where quite literally nobody on the face of the Earth needed more misery and nihilism in their life. I think, whether by coincidence or intention, WE ARE CHAOS manages to give Manson a more positive and enjoyable outlook. There are more than a few moments where he wallows in cynicism and pity, but it doesn’t feel laboured or forced. Strangely, there’s something that feels quite unifying in the way this record progresses and expands. Manson hasn’t been an outsider for a long time and he isn’t trying to be.

Perhaps the most divisive entry in his discography, WE ARE CHAOS is unashamedly Bowie-esque. While portions of this album are a success, and there are some great tracks, I really cannot get along with the mix of this record. There are some extremely strange choices made with the placement of Manson’s vocals in the soundscapes, where he sounds buried and struggling for presence, particularly in tracks like INFINITE DARKNESS. There’s a puzzling moment on HALFWAY & ONE STEP FORWARD where Manson’s vocal track seems to get turned down during the second verse. By this point, I’m getting slightly worn out by the production style in general too. It feels less like Manson is drawing on classic rock influence to shape his own works and more like he’s performing a pastiche of both his own works and the history of the genre.

DON’T CHASE THE DEAD is an enjoyable throwback and Manson is still enjoying a new maturity afforded to him by The Pale Emperor, but I feel very much by this point that Manson needs to find a new angle. I think there are moments where he comes close to it but seems to slightly retreat from fully embracing it, such as the title track where Manson goes full Bowie and angles toward something less personal or introspective and more exterior. It doesn’t fully land for me, mostly because I don’t think Manson has found the perfect mix of individuality and outside influence.

Nothing on here is downright embarrassing like some of his weaker efforts, but by the same token, very little of this material generates much intrigue. I think every artist who sticks around long enough has a wallpaper album, pleasant but unremarkable, and WE ARE CHAOS is Manson’s.

BEST TRACKS: DON’T CHASE THE DEAD / KEEP MY HEAD TOGETHER

Heaven Upside Down

It’s a bit surprising to label Heaven Upside Down as one of Manson’s weaker efforts, especially considering it’s far from a total misfire. While the album may not reach the heights of The Pale Emperor, it still offers plenty of moments worth celebrating. Manson’s ability to reinvent himself and produce engaging material remains intact, though this album does feel like it’s still finding its footing after the success of its predecessor. It throws off the purposeful malaise of The Pale Emperor, but whether it finds a suitable emotional replacement is debatable.

The album opens strongly, with Revelation #12 stripping back some of the more bluesy elements of The Pale Emperor and providing one hell of a tone setter. It’s fast, frenetic, Manson’s vocals are pronounced and strong, it’s great, and then it feels like Manson starts to keep his cards held very tightly indeed. Tracks like Tattooed In Reverse maintain the slick and classy production, but it’s hard to shake the feeling that this album is slightly in awe of the success of its direct predecessor and trying to straddle the line between committing to a new direction and not upsetting the apple cart.

Unfortunately, there are some moments that represent an objective regression. JE$U$ CRI$I$ is mostly real enjoyable, and the back half of the song is just brilliant, the low, throbbing instrumentation providing some real edge to Manson’s howls. His voice still sounds fresh, like he’s rolled back the clock fifteen years. Unfortunately, the song is also home to the worst chorus Manson has maybe ever written, eye-rollingly bad. But pleasantly, this sticks out like a sore thumb precisely because it’s a real misfire on a record that is otherwise hitting the mark.

One thing I enjoy about this record is its confidence. We Know Where You Fucking Live isn’t reinventing the wheel, nor is presenting itself as such: It’s just having fun. Kill4Me has a similar purpose with an enjoyable rhythm and melody, though I think it’s fair to say the writing has taken a decline, with SAY10 being a good example, indulging in a scope or an energy that I don’t think Manson is ever really earning with his lyrics.

This feels like Manson’s take on a pop record, something to be enjoyed on a surface level and yet there are some surprises to be had. Saturnalia feels expansive, glacial and huge. The best moments on this album feel really big and there’s some genuine merit to that. Blood Honey is perhaps the nicest surprise on the album in some ways: THIS is what Eat Me, Drink Me could’ve been!

I think if this album managed to keep anything from The Pale Emperor, it’s the class. This is a collection of songs that I think are objectively more accessible: The Pale Emperor is hardly an esoteric record but one that relies on an audience familiar with Manson’s career, the highs and the lows, for maximal effort.

It’s hard for me to be particularly objective about this era of Manson. By the time this album was released, I was riding so high off the immensity of The Pale Emperor that I think I was always going to give this album more than a fair chance. Heaven Upside Down, in many ways, is a reinvention record for fans who stopped listening to Manson at the turn of the century. It’s a companion album to The Pale Emperor, playing with similar ideas and with a slightly less dense and pronounced sound signature, and a fair few issues. But I think there’s real merit to a lot of this one.

BEST TRACKS: Revelation #12 / Saturnalia / Kill4Me / We Know Where You Fucking Live / Heaven Upside Down / Threats of Romance

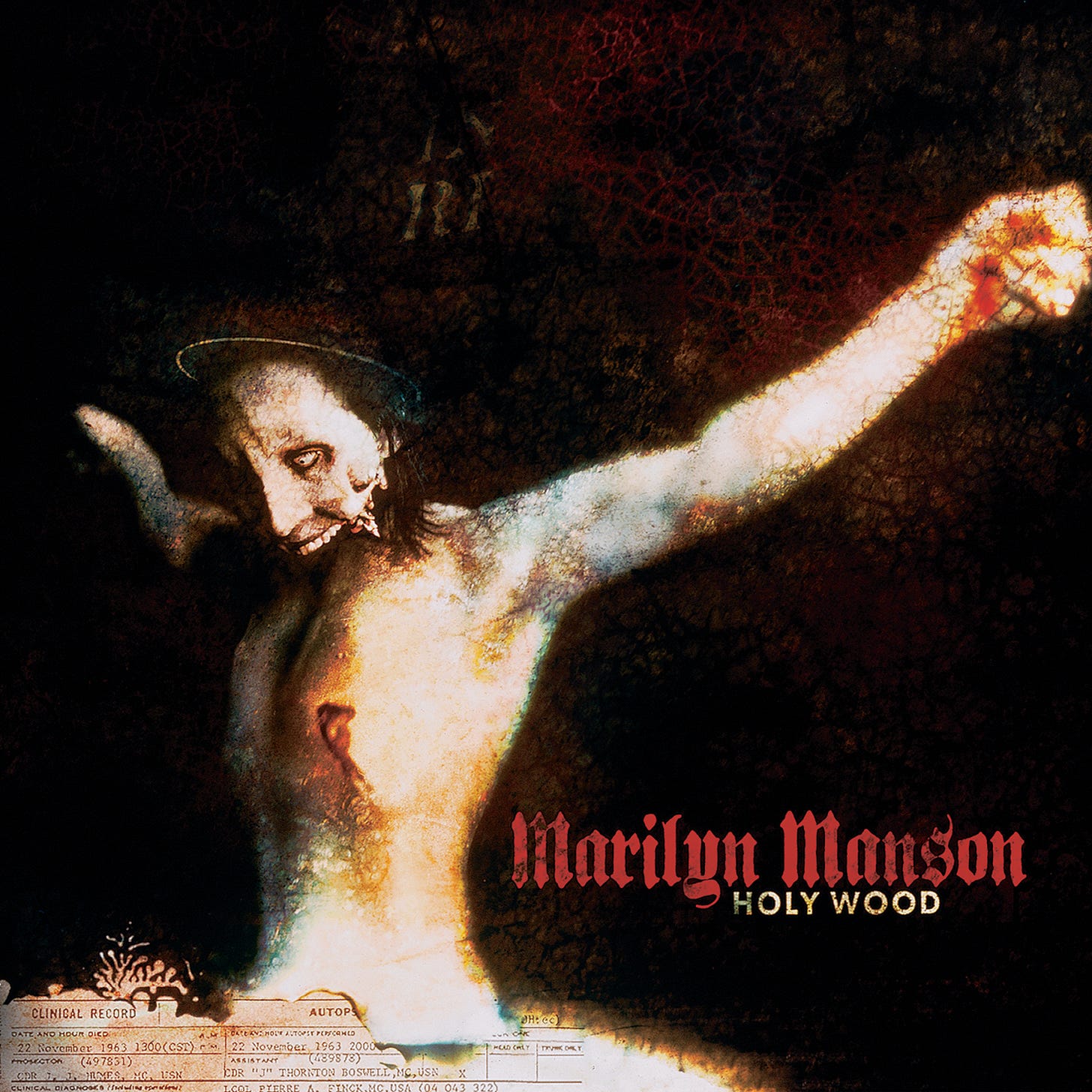

Holy Wood (In the Shadow of the Valley of Death)

With Mechanical Animals, Manson underwent a total aesthetic reinvention, trading his grotesque, industrial menace for neon-soaked glam rock, and the gamble paid off. That success, coupled with the album’s stark departure from his earlier work, meant that when it came time to make Holy Wood, Manson had the rarest of luxuries: complete creative freedom.

Or at least, he should have. Because while Manson had the industry capital to go in any direction he wanted, his public standing had just taken a brutal hit. His unfortunate role as the most identifiable scapegoat for the Columbine High School shooting meant that he was no longer just playing with fire but caught right at the epicentre of the blaze. It’s one thing to wear the aesthetics of danger and darkness; it’s another to be blamed for inspiring two teenagers to massacre their classmates. It didn’t matter that Manson’s connection to Columbine was entirely erroneous, based on quite literally nothing whatsoever; the damage was done.

It’s difficult to say how much of an impact this had on the record when all was said and done. Undeniably, this is one of Manson’s most accessible works, a kind of warped victory lap where Manson attempts to deliver anthem after anthem, and succeeds in part. The first stretch of this album is bombastic and energised, delivering some of Manson’s most viscerally enjoyable tracks (for my money, The Fight Song is one of his best singles ever) but there’s a sense that the edges have been sanded down slightly too much.

One of Antichrist Superstar’s greatest strengths is how it straddles the line between gothic performativity and genuine malice, and I’m sorry, but tracks like In the Shadow of the Valley of Death feel out of place, forcing the momentum to halt for no good reason. There’s a pretty sallow stretch of material after album highlight The Nobodies, where Manson seems to be working through ideas he hasn’t fully mapped out. There’s a version of this album where Manson culls most of the back half (save for a few essential tracks), and it stands shoulder to shoulder with his very best work.

The saving grace of Holy Wood is two-fold: no matter where you are in the record, you’re never too far from one or two really enjoyable tracks in succession, and the first half of the record is simultaneously well-paced and frenetic. But after such a visceral opening fifteen minutes, it feels like Holy Wood is trying to get back on track and never quite finds its groove again. I realise this particular review reads harshly, but to be clear, there is a LOT to enjoy on here. With that said, however, for me this is Manson’s first notable stumble.

BEST TRACKS: The Love Song / The Fight Song / Disposable Teens / Target Audience (Narcissus Narcosis) / “President Dead” / Cruci-Fiction in Space / A Place in the Dirt / The Nobodies / Born Again

Portrait of an American Family

Time for a confession: the decision to write this article is what prompted my first ever full listen to Portrait of an American Family. I’d never carved out time for a full listen, mostly because of its reputation among Manson fans, a fun but ropey grunge-esque shock-rock shlock-a-thon. It’s not hard to see why this opinion has stuck, given that Antichrist Superstar represented such a violent deviation from the mainstream and catapulted Manson from seedy backroom shows in Florida to the biggest rockstar on the planet.

But they’re wrong. Portrait of an American Family, despite its shortcomings, is one of the most frenetic, entertaining albums Manson has ever released. It is undeniable that Manson is taking major cues from the grunge movement, and yet he seems aware that it’s coming to a close, and is within touching distance of something else. The album opens with an incredibly ‘90s spoken word piece, and you’d be forgiven for thinking an Eat Me, Drink Me level disaster was impending. But the most surprising thing about Portrait of an American Family is the levity it treats itself with: you are supposed to find this campy, over-the-top, shlocky. While the album certainly tackles serious topics, there’s an undeniable sense of not taking any of it too seriously, but in a very double-edged way. On one hand, this is an accessible album full of fun sounds and catchy anthems, not an academic paper or a literary masterwork. But on the other hand, a feeling that still holds water today: everything is so fucked that it can’t be fixed.

Unlike Antichrist Superstar’s white-hot nihilism or Mechanical Animals’ glitzy, alienated autopsy of fame, the album doesn't attempt a higher concept or overarching narrative. It’s a tongue-in-cheek ribbing of the total apathy of American culture, Manson demanding that the “white trash, get down on your knees” and continue to consume with no regard for the filth that has infected every facet of consumption in American life. Manson is less a demon from Hell and more a Mad Hatter style curator of a wild ride through a psychedelic glam-punk punch-up. The penultimate track My Monkey is the only one I can mark as a dud, slamming the brakes on the momentum from Snake Eyes and Sissies, though this sin is quickly absolved as Manson closes the record with Misery Machine, which could well be the best track on the entire thing. Even on the tracks where Manson’s lyrics and vocals are slightly spinning their wheels, the instrumentation is sharp and inventive throughout, with some serious groove always shoving its way to the forefront.

While the bare bones of Antichrist Superstar and later efforts appear in pieces across the record, this is a unique entry in Manson’s discography that deserves its flowers. All the impotent defenses of utter dross like Eat Me, Drink Me and The High End of Low should instead come to Portrait of an American Family’s aid and provide this album with the reappraisal it wholeheartedly deserves. Easily the nicest surprise this deep dive has provided.

BEST TRACKS: Cake and Sodomy / Lunchbox / Dope Hat / Get Your Gunn / Dogma / Snake Eyes And Sissies / Misery Machine

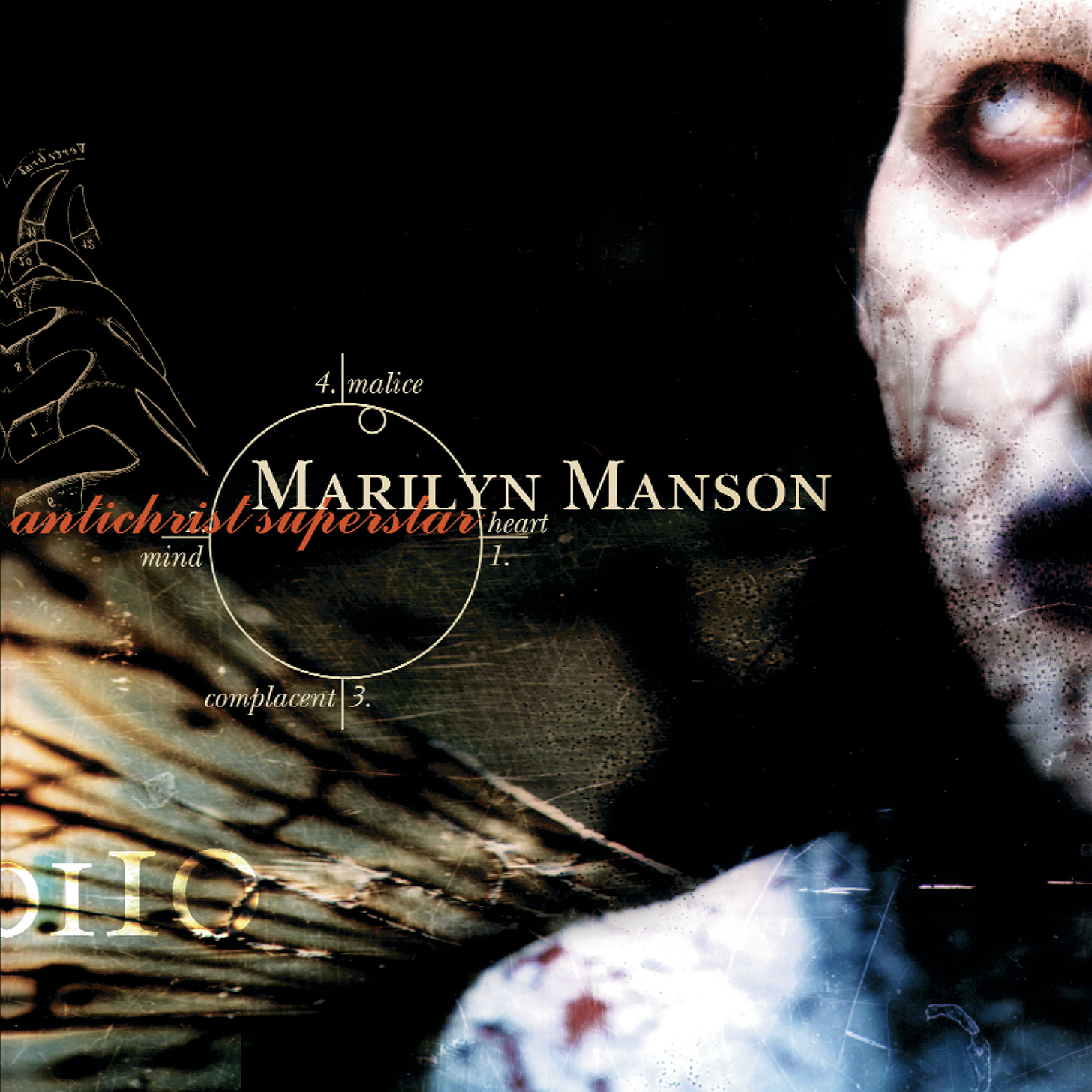

Antichrist Superstar

It’s hard to listen to Portrait of an American Family and come away with a clear idea of where Marilyn Manson might go next. Their debut effort has some real heaviness and subversive ideas, but can’t quite step out of the shadow that grunge had cast over the rock landscape of the ‘90s. But while Cobain’s death in 1994 undoubtedly changed the genre’s trajectory, it wasn’t a death knell. Nirvana may have ceased to exist on the 5th April 1994, but their contemporaries were still going strong. Alice in Chains’ eponymous third album topped the Billboard 200 on its release in 1995 and Pearl Jam’s No Code (released some three months before Antichrist Superstar) achieved the same milestone. Both were huge sellers, but both were similarly marked for feeling dated and uninteresting, fairly or not. Grunge was on life support, waiting for its inevitable end.

In 1996, Marilyn Manson released Antichrist Superstar, torched the remains of grunge, and danced in the ashes. Far from Cobain’s self-loathing, flannel-clad caterwauling or Soundgarden’s towering power ballads, Manson was a filthy, perverse, and downright frightening reanimation of glam rock. Grunge was, at its core, a reality-fantasy, young men who looked normal and became reluctant global icons. Manson was a rail-thin, deranged iconoclast who claimed to be the antichrist — and played the part to perfection.

He didn’t shy away from the spotlight; he demanded to be seen, to be gawped at. As America teetered on the edge of a full-blown culture war, Manson almost singlehandedly reignited the Satanic Panic of decades past and made himself public enemy number one.

Antichrist Superstar is ostensibly a concept album, imagining a rockstar who destroys the “world”, whatever that may be. While there’s endless write-ups on the influences and hidden meanings to much of the album, the story is relatively straightforward. But beyond the narrative, Manson’s second album is a maelstrom of furious nihilism. There’s little left in terms of camp and shlock, and this departure from the messy psychoactive glitz of Portrait Of An American Family is undoubtedly the most important tonal shift of Manson’s career. It’s undoubtedly messy, and like the vast majority of Manson’s albums, it’s frontloaded. Several songs in the middle section blur together—not because they sound alike, but because they lack presence. The highs here are numerous though, from the immediate explosion of Irresponsible Hate Anthem to the eerie nursery-rhyme style Cryptochid or the anthemic title track, and that’s all without mentioning The Beautiful People, undoubtedly Manson’s most iconic song ever. This isn’t just the peak of the band’s cultural power and commercial success, but a genuinely important landmark in contemporary musical history.

BEST TRACKS: Irresponsible Hate Anthem / The Beautiful People / Dried Up, Tied, And Dead To The World / Tourniquet / Little Horn / Mister Superstar / 1996 / Minute of Decay / The Reflecting God

The Pale Emperor

2015 should’ve been a year that saw Manson release another largely ignored artistic misfire. There was very little in the last ten years to suggest Manson had anything other than one or two interesting ideas per studio project left to offer. The self-proclaimed antichrist superstar had gotten fat and lazy. His musical output had become hackneyed. His live shows were becoming an embarrassment, and he seemed caught in a paradox—realizing he was no longer an imposing cultural shockwave while desperately trying to recapture that infamy despite continued failure.

It seems that he finally realised that it is simply not possible for a middle-aged man who’d been famous for nearly two decades to inspire much fear in anyone. So he stopped. Instead, he embraced a new sound and found complete reinvention in The Pale Emperor. This is not simply Manson finally rediscovering his form, but reaching a new artistic peak. Gone are the costumes, the posturing, the endless chase of a youth that had long since passed. This is a one-time cultural titan finally accepting that, at least as far as his cultural presence is concerned, he’s little more than a memory, a relic of a by-gone era, the anti-hero of a micro-period now looked back on as slightly absurd, almost laughable in hindsight. The mighty US of A was scared of this guy?

An emperor made pale by creative decay? Cultural translucence? Age? Perhaps it’s all of these things, and Manson takes the internal to task as harshly as he did the external world in his hayday. But this is not a has-been rolling over, showing his belly to the world and saying ‘yes, you’re right, I’m a loser and I suck now’. In Manson’s own words, “The past is over / Now passive seems so pathetic”.

I view this as a tacit admission that Manson has failed to put his best foot forward for several years. Since The Golden Age of Grotesque, he’s failed to find an evolution to his signature sound that provides the genesis for a creative reinvention. But now, backed by lingering guitars and thumping percussion, The Pale Emperor feels like a defibrillator, shocking Manson into the kind of artistic freneticism he’d been lacking since the turn of the century.

The production across the album is not only inventive, but indulgent in a way that provides some real catharsis. There’s real class here too, particularly in the percussion that undercuts every song with so much natural swagger and confidence. Manson, too, sounds fantastic across the record, matured and full-bodied. From the agonising howls on Third Day of a Seven Day Binge to the snarling self-condemnation on Deep Six, it’s like an entirely different person has inhabited Manson’s voice and energised him, like "a stranger had a key, came inside my mind / And moved all my things around”. Manson’s nauseating love-affair with endlessly-layered vocals, which endlessly drowned even the most impressive production work, are largely absent here, his voice powerful and laid bare. Everything in the instrumentation and mix is so cleverly balanced here, never leaving Manson adrift in the heavy instrumentation and never hanging him out to dry.

It’s difficult to find a more fitting metaphor than this: Manson is a man who went to bed at twenty-seven, and didn’t realise he’d aged a day until 2015. The Pale Emperor is so fresh and classy and weighty that it makes everything post-Eat Me, Drink Me feel worth it. If The Pale Emperor was the payoff for Manson’s noughties output, then consider that a deal well done.

In many respects, this is Manson’s Blackstar, a full-throated acceptance of his mortality. Manson isn’t just opining his emotional vulnerability to hollow instrumentation before retreading old ground, but putting everything out on the table, even his trepidations about allowing himself to be open and honest, being “open too much”.

The Pale Emperor is not only a worthy successor to Manson’s greatest albums, but the first time since Mechanical Animals that his music has represented a triumphant full-blown reinvention. Manson is done with chasing the highs of yesteryear, wallowing in pity and basking in self-reflected glory. Manson hasn’t just finally found something new to say, but has provided plenty of reasons to hear him out.

BEST TRACKS: Killing Strangers / Deep Six / Third Day Of A Seven Day Binge / The Mephistopheles of Los Angeles / Warship My Wreck / Slave Only Dreams To Be King / The Devil Beneath My Feet / Odds of Even

Mechanical Animals

By 1998, Marilyn Manson was an American household name. Within two years and with just one studio album reaching the mainstream, he had become the poster-boy for moral panic, an emaciated freak who’d seemingly appeared overnight and turned the world upside down. Fans of the band expected everything to get heavier, nastier. Antichrist Superstar is certainly heavy, but Manson had smashed pop culture wide open with a level of overt subversion rarely seen before. It only made sense that he’d double down and shift the window even further.

In a way, he did. But he managed to do it in a way that surprised everyone and alienated more than a few. Just as the public fixated on Manson as a skeletal demagogue corrupting America’s youth, he reemerged as something entirely different: an entirely artificial pop star from the stars called Omega.

If you compare images of Manson from 1997 to 1998, there’s a stark difference. Many people draw the obvious comparison to Ziggy Stardust, but often as a point of critique or dismissal, that Manson was simply echoing the artistic calls of yesteryear. This is entirely fair on the surface, but I think this criticism ignores Manson’s intentional references to the past.

Omega is supposed to be deeply evocative of Ziggy Stardust. Where Manson’s glam rock persona separated from Stardust was in its deeply strange eroticism. Omega was bright and colorful, with a slight gothic edge and often sported skintight lycra: Omega also had fake breasts and too many fingers. It’s easy to read that and write it off as Manson being edgy in a very teenage way, but I don’t think it was supposed to be edgy for the sake of it. There’s a weird invocation of the markers of traditional sexual appeal, woven into things that didn’t seem quite human. This was an image of sexuality that had been warped slightly too far, and this idea of excess ad absurdum is a major factor in the narrative of Mechanical Animals.

Ziggy Stardust sees an androgynous rockstar fall to Earth as a would-be saviour to the people before his own ego condemns him. It is ultimately about a man who arrives to fix a system before succumbing to it himself. He is a hopeful figure destined to change the world who is defeated by himself.

Mechanical Animals sees an androgynous figure fall to Earth before becoming quickly swept up into an industry of fast and filthy excess. Ultimately, Omega is swallowed entirely and becomes another cog in a system that had no need nor desire for a saviour. Omega is entirely constructed to fit the strange world of Mechanical Animals, manufactured to perfection.

I’m not making the argument here that Mechanical Animals is nothing like The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, quite the opposite. In many ways, it’s the core concept of Ziggy Stardust, repurposed and refitted. It’s louder, more raw and ultimately more hopeless. Ziggy Stardust offers a chance at change, Mechanical Animals offers nothing of the sort.

This was hugely upsetting to a considerable portion of Manson’s fanbase, a betrayal of his raison d’etre. But with the benefit of hindsight, Manson’s decision to commit to a complete one-eighty, both aesthetically and musically, was the single best choice he ever made. Antichrist Superstar, in my opinion at least, manages to deliver a dose of genuine malice that doesn’t overstay its welcome. How exactly could a man who now had a seat at the table replicate the feeling of that record? It is distinctly counter-culture and, really, it was Manson’s attempts to recapture that danger across the noughties that led to his artistic nadir. It’s a trick you get to play once.

So Manson didn’t play it again. Instead, he gave us Mechanical Animals, a distinctly digital window into the destructive excess of fame. The aforementioned narrative at play isn’t particularly obvious, nor is it a strict structural framework. But I think the point of this album is that the narrative is secondary to the excess. The story is struggling to be told through a drug-fuelled haze of apathy. Tracks swell to their crescendo and sputter out into digital noise, moving through perspectives and emotions wildly. Great Big White World starts an expansive vision of falling down to Earth before The Dope Show slams us immediately into a decadent vision of the top of the mountain, and the album oscillates between these two worlds constantly. The titular track is one of a few that bridge the gap, but one of the most striking things about Mechanical Animals is how certain tracks like The Speed of Pain feel like pockets of warped lucidity in a maelstrom of glitzy, clinical decadence when set against tracks like Disassociative.

And Manson manages to handle all of this while making Mechanical Animals eminently listenable. Between traditional rock songs like Rock is Dead and Coma White or tongue-in-cheek anthems like I Don’t Like The Drugs, But The Drugs Like Me and I Want to Disappear, you’re just having a hell of a lot of fun from start to finish. Manson never lets the consequences of this fun get too far in the rear-view mirror, though, and I think that’s what elevates this record from a good one to a genuinely great one.

There’s a cohesion to this record Manson never quite captured again. It’s a deeply enjoyable record with some pithy remarks, some genuinely sombre moments and a rich tapestry of excess and indulgence. Even the moments that don’t entirely land for me hold some objective merit in their furtherment of these themes and I can appreciate their value. In many ways, this backlash to this album and its then-historic descent from the charts probably caused Manson’s regression and stagnation and I think that is a terrible shame, because this record is a genuinely engrossing picture of the lonely, lonely summit. But perhaps that’s a fitting endpoint.

BEST TRACKS: Great Big White World / The Dope Show / Mechanical Animals / Rock Is Dead / Disassociative / Posthuman / I Want to Disappear / I Don’t Like The Drugs, But The Drugs Like Me / New Model No. 15 / Coma White

And we’re done!

This was a lot of fun to put together. At points, it was also deeply painful and draining. I’m endlessly grateful to anyone who managed to get their way through an article that started as a general retrospective and then spiralled into this. It’s difficult for me to find topics that I’m interested in writing at length about sometimes, mostly because I come up with a general idea of time and effort required and vastly exceed those boundaries very quickly. Thankfully, this didn’t happen with this one and, if nothing else, I’m pleased I managed to commit to an ambitious amount of work and just about crawl over the finish line.

I’m also extremely pleased that I can stop now. Don’t expect to see articles of this size of scope ever again.